The mystery of how birds navigate is over

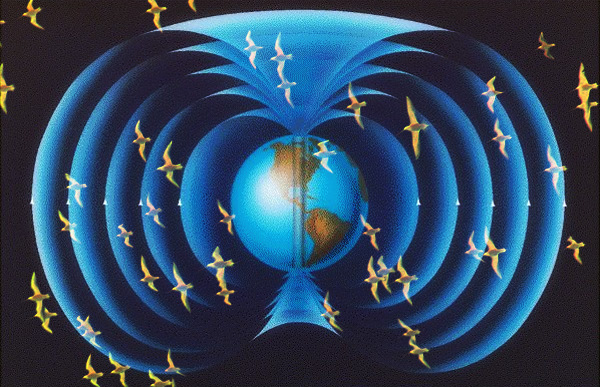

One of the longest running mysteries is exactly how birds navigate when they fly south for the winter or back come spring. For forty years, scientists have known that birds can somehow sense the magnetic field and navigate by it. But they’ve been unable to figure out how, until now. Two teams have recently identified that birds can actually visualize the magnetosphere.

For a long time, the prevailing theory was that cells rich in iron in bird’s beaks aided their navigation. Then, in the late 1960s, Klaus Schulten proposed that migratory animals, including birds, must contain a certain molecule in their eyes or brains that responds to the magnetic field.

Now it seems, these two teams have made it the prevailing theory. The Swedish study and the German one focus on a class of proteins known as cryptochromes.

Each team discovered a particular type of cryptochrome protein in birds’ retinas known as Cry4, which is sensitive to blue light—including that given off by the Earth’s magnetic field. Both plants and animals are known to contain photoreceptive cells that respond to blue light, which are necessary for circadian rhythms. Yet, this is the first time magnetoreception has been discovered in animals.

A bird’s visual magnetic detection cells rely on quantum coherence. It’s interactions with the quantum field that allows migratory birds to navigate, according to biologist Atticus Pinzon-Rodriguez, at Lund University. Recent research indicated three possible cryptochromes, Cry1, Cry2, and Cry 4, may be involved. Scientists in both teams looked at the gene expression associated with each protein.

They found that Cry1 and Cry2 expression fluctuated throughout the day—as they’re both tied to circadian rhythms, Cry 4 didn’t. It stayed constant. As this gene's protein is being consistently produced, researchers believe it’s tied to detecting the magnetic field. Consider that birds navigate by it day or night. There are other indicators too. European robins for instance, were shown to have increased Cry4 expression during the migratory season, something that wasn’t found in chickens.

Both teams, in addition to looking at gene expression, found that the area in the birds’ retinas where Cry4 is located receives a lot of light. Though the evidence is compelling and the theory strong, more research must be done, particularly in bird species with latent Cry4, in order to confirm these results. And beyond that, scientists if they prove the theory true, will then have to discern exactly how birds perceive the magnetic field.

English

English Arabic

Arabic