Scientists accidentally create mutant enzyme that eats plastic bottles

Scientists have created a mutant enzyme that breaks down plastic drinks bottles – by accident. The breakthrough could help solve the global plastic pollution crisis by enabling for the first time the full recycling of bottles.

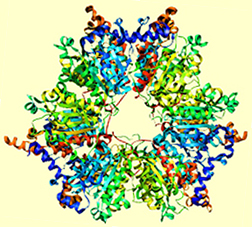

The new research was spurred by the discovery in 2016 of the first bacterium that had naturally evolved to eat plastic, at a waste dump in Japan. Scientists have now revealed the detailed structure of the crucial enzyme produced by the bug.

The international team then tweaked the enzyme to see how it had evolved, but tests showed they had inadvertently made the molecule even better at breaking down the PET (polyethylene terephthalate) plastic used for soft drink bottles.

The mutant enzyme takes a few days to start breaking down the plastic – far faster than the centuries it takes in the oceans. But the researchers are optimistic this can be speeded up even further and become a viable large-scale process.

“What we are hoping to do is use this enzyme to turn this plastic back into its original components, so we can literally recycle it back to plastic,” said McGeehan. “It means we won’t need to dig up any more oil and, fundamentally, it should reduce the amount of plastic in the environment.”

The structure of the enzyme looked very similar to one evolved by many bacteria to break down cutin, a natural polymer used as a protective coating by plants. But when the team manipulated the enzyme to explore this connection, they accidentally improved its ability to eat PET.

One possible improvement being explored is to transplant the mutant enzyme into an “extremophile bacteria” that can survive temperatures above 70C, at which point PET changes from a glassy to a viscous state, making it likely to degrade 10-100 times faster.

Enzymes are non-toxic, biodegradable and can be produced in large amounts by microorganisms,” he said. “There is still a way to go before you could recycle large amounts of plastic with enzymes and reducing the amount of plastic produced in the first place might, perhaps, be preferable. [But] this is certainly a step in a positive direction.”

English

English Arabic

Arabic