A bacterium can withstand 1,000X as much radiation as would kill a human

The world's toughest bacterium classified as an extremophile, a living thing capable of surviving and thriving in conditions too hot, cold, or chemically antagonistic for the majority of life on Earth. Its toughness is so renowned, it's even been called "Conan the Bacterium."

D. radiodurans is the bacterium uniquely resistant to radioactivity. Where 1,000 rads would kill a human within a couple of weeks, D. radiodurans can survived 1 million rads without breaking a sweat. At 3 million rads, significant numbers of the bacteria die, but a few still manage to survive. It's even been found on the walls of nuclear reactors.

But D. radiodurans isn't exactly shielded from radiation. When the small particles emitted by radioactive material shoot through living things, they tear up the DNA and proteins that life uses to function, ultimately destroying cells or causing them to mutate in unusual and unhealthy ways.

D. radiodurans, like all life, is susceptible to this. But it excels at repairing the damage. All life can repair damage to their DNA to some extent, but D. radiodurans is so gifted at this process that it can take a dose of radiation that would kill you, or me, in literal seconds and be as healthy a bacterium as ever a day later.

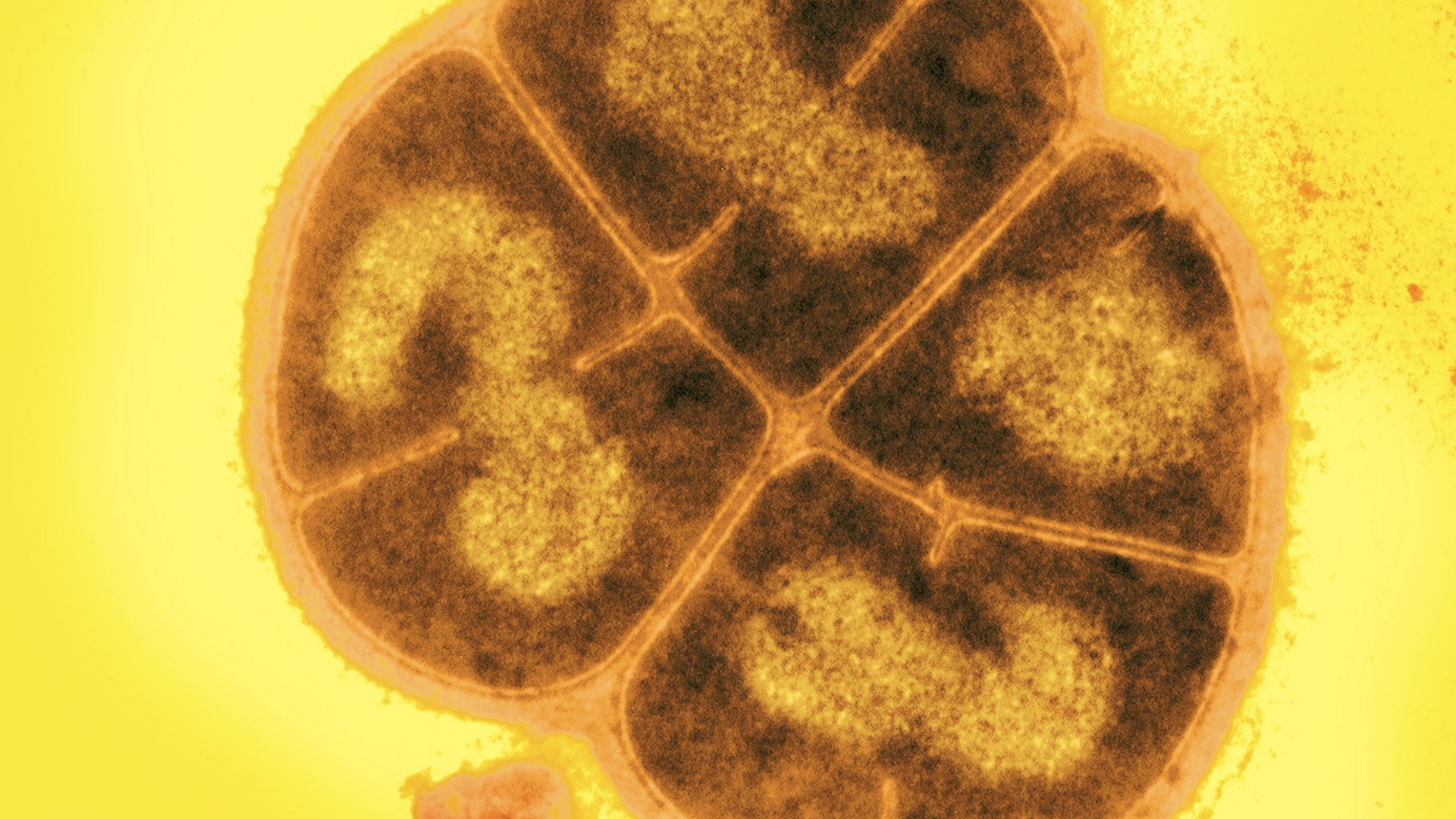

D. radiodurans's trick to this remarkable durability is to have multiple copies of its chromosome and DNA repair molecules, enabling it to quickly take a similar strand of DNA and write it over the damaged kind.

Obviously, a bacterium this unique offers some exciting opportunities to humanity. First, it could be used for bioremediation, or the process of using microorganisms to clean up contaminated environments. In areas with high radioactivity, it can be and has been genetically modified to consume and digest heavy metals or other toxic materials. It's incredible ability to repair its DNA is of interest to researchers looking into slowing down the human aging process — which is really just accumulated DNA damage — or improving our resistance to radiation and cancer.

More whimsically, it could be used as a means of storing information to retrieve later after a nuclear apocalypse.

Maybe after all the bombs go off and we're all hiding in our basements from the irradiated, massive, and mutated insects that roam the nuclear wasteland, we'll be able to read D. radiodurans's DNA in search of a friendly message from the past.

English

English Arabic

Arabic